The devastating toll of COVID-19 in nursing homes across the country has drawn attention to the fact that many workers in long-term care work at multiple facilities because they need more than one job to make a living, and this has directly contributed to the tragedy that is currently unfolding. Unfortunately, long-term care workers aren’t the only ones who can’t support their families with a single job. Having to work multiple jobs is a common reality for too many people in BC.

The pandemic is shining a light on the deep inequalities that exist in our economy, which have left some people much more exposed to risk and much less prepared to weather the crisis than others. While on the surface BC’s job market seemed strong going into the pandemic, with low unemployment and plentiful job vacancies (even prompting some to warn of worker shortages), beneath the surface structural problems abounded.

One of the most striking findings of our survey is how common it is for workers—in all regions of BC— to hold multiple jobs.

To take a closer look at these structural inequalities, we commissioned a detailed survey of British Columbians’ experiences with employment. Conducted late in 2019—near the peak of BC’s job market strength pre-pandemic—our survey provides a useful pre-crisis baseline. The results reveal that many BC workers were precariously employed and faced large gaps in workplace protections that have been magnified by the current crisis.

One of the most striking findings of our survey is how common it is for workers—in all regions of BC— to hold multiple jobs. But the survey reveals that some people are more likely to work more than one job than others, with the most notable differences related to age, income, racialization and immigration status, and access to more stable forms of employment.

Almost one third of BC workers aged 25 to 65 had more than one job

Twenty nine per cent of BC workers aged 25 to 65 reported having worked multiple jobs at the same time in the last 3 months with a slightly smaller number doing so at the time of the survey (22%).

Working multiple jobs is by nature fluid and hours at any one workplace can vary significantly week to week, which is why focusing on a 3 month time period provides a fuller picture of people’s experience in the job market than a snapshot taken at a particular point in time.

Our survey found that working multiple jobs was not confined to major urban centres where the cost of living is highest. While Vancouver had a higher proportion of people working more than one job (35%) than the rest of the municipalities in the Metro Vancouver area, Metro Vancouver as a whole had a strikingly similar share as did Northern BC, the Interior and Vancouver Island.

Younger, racialized and low-income workers more likely to hold multiple jobs

Workers aged 25-34 were twice as likely to have worked multiple jobs than those aged 55-65 (39% vs 20%), though even among the older age group a striking 1 in 5 workers reported multiple jobs.

Workers who are racialized were more likely to be working multiple jobs than non-racialized survey respondents (33% vs 28%). Nearly half of respondents who were permanent residents (46%) and more than half of those with temporary status in Canada (54%) reported working multiple jobs compared to 28% who were Canadian citizens. Men were more likely to work more than one job than women (31% vs 27%).

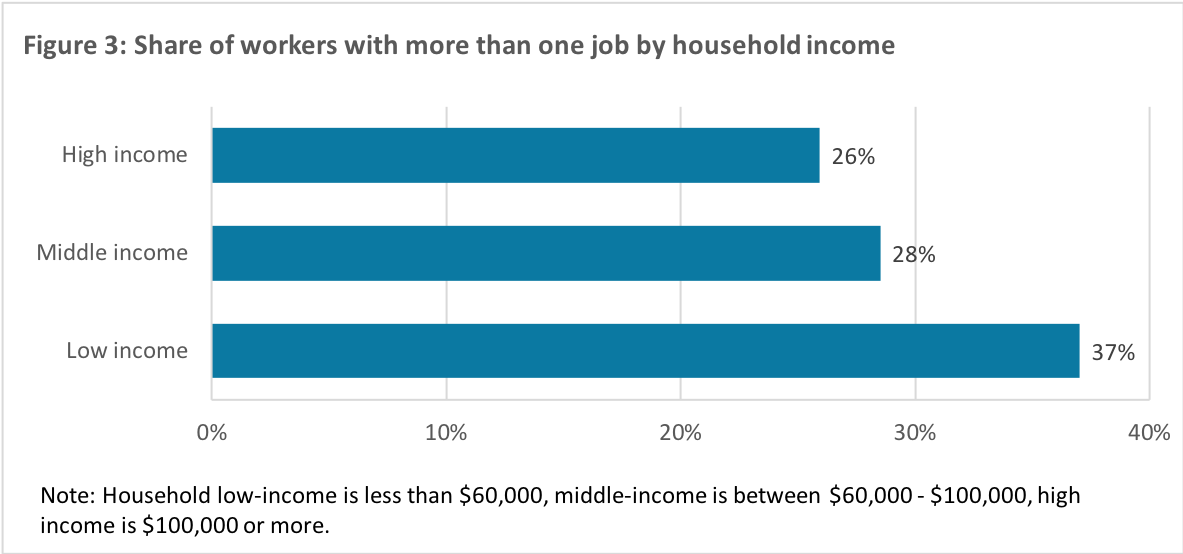

Workers who reported lower household incomes were more likely to work multiple jobs than those with higher incomes, which suggests that the “choice” to take on more than one job is likely driven by financial pressures and low wages and/or insufficient hours.

Nearly half of workers who were enrolled in post-secondary education reported working multiple jobs compared to just over a quarter of those who were not students. However, students were a minority of our sample aged 25 to 65 and the vast majority of BC workers holding multiple jobs (80%) were not simultaneously pursuing post-secondary education.

Workers who reported lower household incomes were more likely to work multiple jobs than those with higher incomes, which suggests that the “choice” to take on more than one job is likely driven by financial pressures and low wages and/or insufficient hours. However, a large number of middle- and higher-income workers also reported having multiple jobs. The survey doesn’t tell us exactly why this is the case but it is likely related to BC’s high costs of living, especially housing, or it may be a sign that workers at every income level are facing less secure job opportunities.

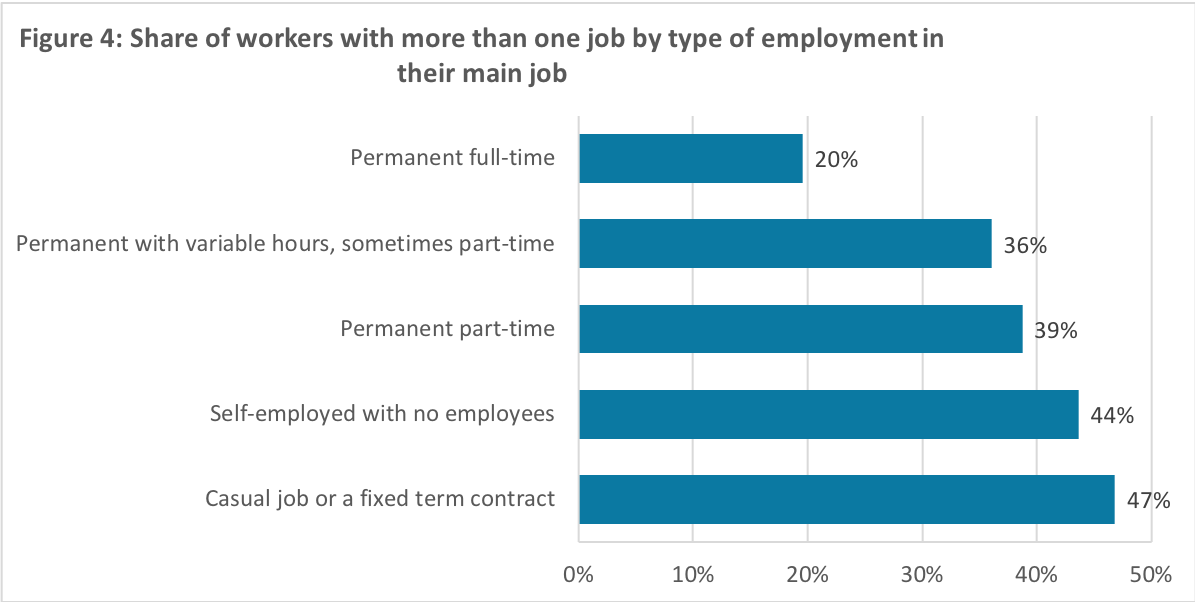

Type of contract in primary job closely linked to whether workers take on additional work

Workers whose main job (the one that paid the most) was a casual position or a fixed-term contract were more than twice as likely as those in full-time permanent employment to work more than one job. This may help explain why we found so many middle- and higher-income workers with multiple jobs as contract-based positions that lack job security become increasingly common across all sectors of the economy.

Self-employed workers with no employees were also much more likely to have more than one job than permanent full-time workers, as were permanent part-time workers (including those whose hours varied between full-time and part-time).

Those working more than one job were equally likely to be in the private sector as the broader public sector (including schools, hospitals and seniors care facilities) for their main job, and slightly more likely to work in the non-profit sector. These workers were less likely to have employer-provided benefits than their counterparts with only one job, and less likely to be paid if they miss a day of work (for example, because of illness). They were also slightly more likely to be renters, though that difference is fairly small.

Why working multiple jobs is more common than we knew, and what we should do

The number of workers reporting multiple jobs in our survey is much higher than the official figures from Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey, which shows only 7% of British Columbians—or one of every 14 workers—working multiple jobs at the same time in 2019. The official statistics have barely budged in the last 20 years, despite the rise of gig work and the casualization of many jobs, raising questions about whether the Labour Force Survey is accurately capturing the realities facing Canadian workers.1 Without up-to-date accurate data, we can not monitor how different workers are being impacted by economic challenges such as the current crisis nor can we develop effective public policy that supports them.

Some BC workers were already vulnerable before the crisis hit and were ill prepared to cope with loss of employment income. Those in temporary, casual and part-time jobs and those who were lower-paid saw the largest drop in employment and hours worked in March. Many of them would have lost much of their income as a result of COVID-19 without necessarily being laid off from all jobs. This is why extending the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) to cover people earning up to $1,000 a month was vitally important at the time when much of the economy was in a near lockdown.

Without up-to-date accurate data, we can not monitor how different workers are being impacted by economic challenges such as the current crisis nor can we develop effective public policy that supports them.

However, as BC begins to gradually reopen, it is crucially important to ensure the economic security of these vulnerable workers. People who needed more than one job to make ends meet might be recalled to one but not all of their workplaces, and for many low-wage workers it might mean returning to less income than they had previously or while receiving the CERB.

The CERB has set a de facto standard that Canadians consider the minimum needed to live on, and returning to work should not put people below that income. Yet, a minimum wage worker in BC needs 144 hours of work in a month—more than 4 weeks at 35 hours per week — to earn $2,000. BC’s minimum wage increase scheduled for June 1 will help a little, but many workers will need more support, especially those who are unable to find full-time work during the partial reopening phase of the pandemic. Options for extending additional CERB coverage to those earning between $1,000 and $2,000 per month should be considered.

We need to rethink how our labour market is structured to ensure that paid work allows people to keep a roof over their head and food on the table without having to juggle multiple jobs.

In the medium-term, we need to rethink how our labour market is structured to ensure that paid work allows people to keep a roof over their head and food on the table without having to juggle multiple jobs. In their pursuit to keep labour costs low, employers have become overly reliant on part-time positions and temporary contracts, which generally enable them to pay workers less and offer fewer (if any) benefits than they would for full-time, permanent jobs. While we may not be able to change this situation overnight, one way to mitigate the negative effects of such job insecurity is instituting precarity pay, a wage premium for jobs that aren’t permanent full-time. The practice is used successfully in Australia, where it is known as ‘casual loading’ and requires employers to pay a 15-25% premium on top of equivalent permanent, full-time wages to workers who don’t have a firm commitment of the days or hours they will work, or their length of employment.

We also need to overhaul our system of workplace rights, protections and benefits, which is based on the outdated assumption that people have a permanent job with a single employer providing benefits. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown how programs like Employment Insurance (EI), and benefits like paid sick days, are not available to enough people—including the essential workers we all depend on. The temporary CERB has been welcomed because it extends coverage to many who would have been ineligible for EI, but we need to look at expanding these emergency programs to support people beyond the immediate crisis.

It would be unconscionable to go back to the old ‘normal’—where too many people are forced to work multiple jobs, have few workplace benefits or job security, and end up going to work sick because they can’t afford to miss a day’s pay. We need a new normal where everyone has access to stable, decently-paid employment with protections and rights that support a good quality of life.

CCPA-BC commissioned this survey on precarious work in partnership with SFU’s Labour Studies Program. The internet-based survey was administered by Insights West in the fall of 2019 to British Columbians between the ages of 25 and 65 who had worked for pay in the previous three months. The survey, which replicated elements of the PEPSO survey of workers in Ontario, was designed to collect more information on job quality and workers’ experiences of insecure and precarious employment than Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey covers. A total of 3,117 qualified respondents completed the survey. Weighting was applied to the data according to Statistics Canada 2016 Census figures on region, age, gender, ethnicity and among the Chinese and South Asian populations, country of birth and time in Canada among immigrants to ensure it is representative of the working BC population between the ages of 25 and 65. A true probability sample of this size would have a margin of error of plus or minus 1.8% 19 times out of 20.

We thank the following organizations for their financial support of this research: Vancity Credit Union, the Vancouver Foundation, BC Federation of Labour, Federation of Post-Secondary Educators of BC, the Lochmaddy Foundation and UBC Sauder School of Business.

Notes

1 Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey (LFS) is the official source of monthly estimates of total employment and unemployment in Canada. The reference period is usually the week containing the 15th day of the month and the LFS asks whether the worker had “more than one job or business last week” in addition to asking a few more questions related to the person’s “other job or business” (thus assuming there is only one). In 2020 the LFS added a new question asking respondents to specify the total number of jobs worked in the reference week though data has not yet been released from this question. In these official statistics, British Columbian workers are slightly more likely to work multiple jobs than their counterparts in most other provinces (except Saskatchewan and Manitoba).