The COVID-19 pandemic has made it clear that everyone’s health and well-being depends on workers being able to stay home when they are sick. In BC, workers now have a legal right to time off when they are ill—three days for regular illness and unlimited time for COVID-19—but not paid time off. As a result, for many in BC, staying home when sick means losing income.

It is profoundly unfair to force workers to make an impossible choice between working sick and staying home without pay. It is also an ineffective public health strategy that will inevitably result in employees reporting to work ill and potentially triggering outbreaks of COVID-19, as we saw recently at BC chicken processing plants.

It is encouraging to see the federal government initiate talks with the provinces to look at implementing 10 days of paid sick leave across the country after pressure to take action came from other leaders, including BC’s premier and the federal NDP leader. As our research shows, such policies would benefit a large number of workers in BC, including some of the lowest paid and most precarious.

While many unionized workers have access to paid sick time negotiated through collective bargaining and some non-unionized workers have paid sick time provided as a benefit from their employer, access to paid sick leave is far from universal. Implementing a paid sick leave policy will have positive impacts for many employees across the country who are not currently covered. Exactly how many is challenging to answer as we collect very limited data on employer-provided benefits in Canada (more on that below). To fill that information gap we asked about access to paid sick leave in our recent BC Employment Precarity Survey. Conducted late in 2019—near the pre-pandemic peak of BC’s job market strength—our survey provides a useful pre-crisis baseline.

More than half of BC workers don’t have access to paid sick leave

Our survey reveals that just over half (53 per cent) of workers in BC aged 25 to 65 do not have any paid sick days. The lack of access to paid sick leave in BC is shocking but it is consistent with the data from the 2016 General Social Survey which found that only 42 per cent of Canadian workers had paid sick leave at the time. Our survey shows slightly higher access to paid sick days because it focuses on the core workforce (ages 25 to 65) and leaves out younger and older workers who are even less likely to be covered by paid sick leave provisions.

Even in the US, a country that is hardly friendly to workers’ rights, a considerably larger proportion—76 per cent of workers—have some paid sick leave. This isn’t because US employers are more generous than Canadian ones, it’s the direct result of government policy. Twelve US states and the District of Columbia have legislated mandatory paid sick time provisions while in Canada only Quebec and PEI require employers to offer any paid sick leave (two and one day per year, respectively). The Canada Labour Code mandates three paid personal days per year but this applies to federally regulated workers only. Federally regulated workers, however, represent a small fraction of the labour force and include workers in banks, marine, rail, air transportation and telecoms, among others.

“It is profoundly unfair to force workers to make an impossible choice between working sick and staying home without pay.”

Leaving the provision of paid sick leave to employers’ goodwill has clearly not been sufficient. A legal requirement to provide paid sick leave is the only way to extend coverage widely.

Mandating paid sick time would level the playing field for the good employers that are already making this benefit available while having to compete with employers that are cutting costs by not providing paid sick leave. Mandatory paid sick leave requirements would also benefit those who currently don’t have access—some of the lowest-paid and most precariously employed workers in the province.

Low-income workers least likely to have access to paid sick leave

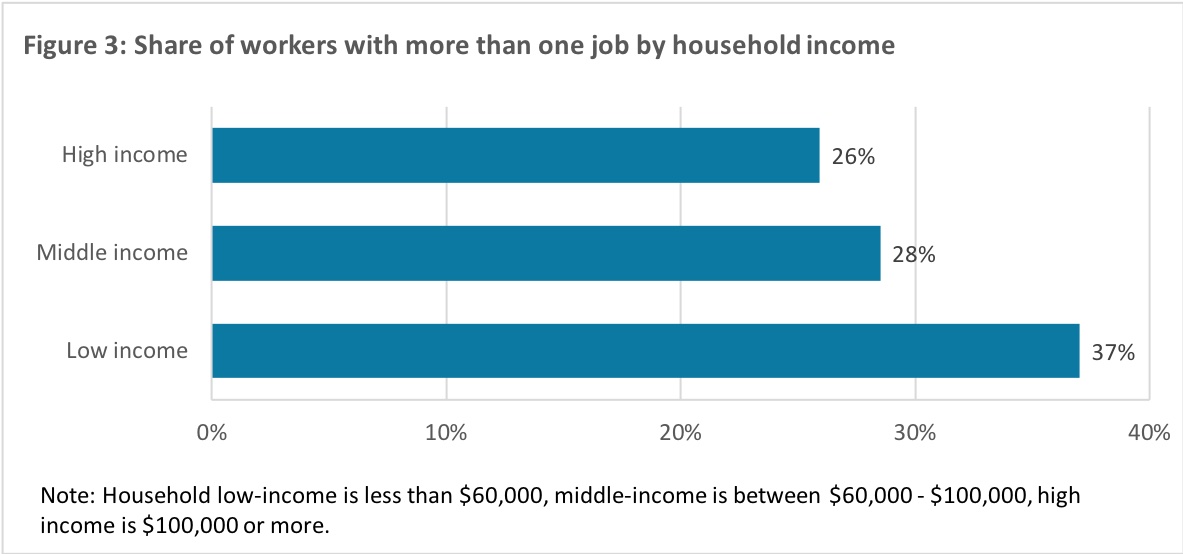

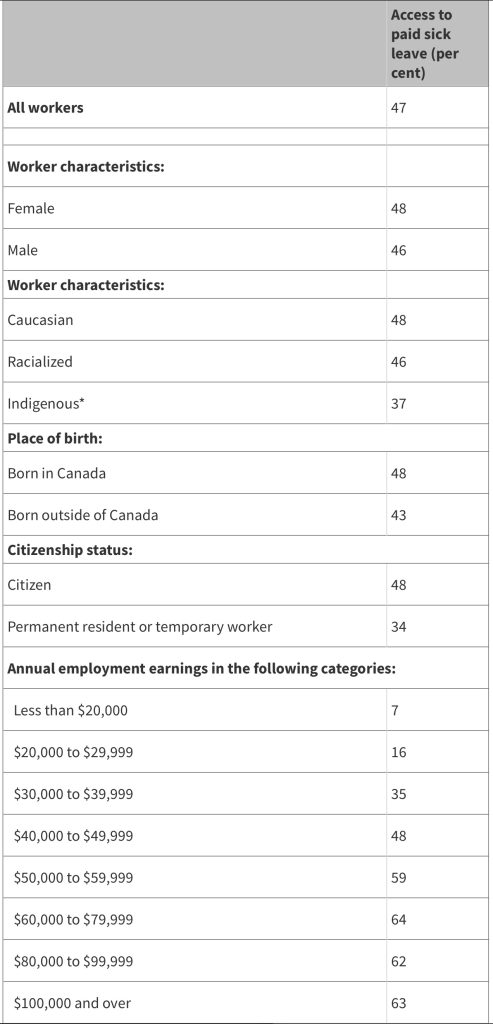

Our survey allows us to take a closer look at which groups of workers do not have access to paid sick leave. Workers who reported low annual employment earnings were much less likely to have access to paid sick leave than higher-income workers. The numbers are shocking for the lowest-paid workers earning less than $30,000 per year where an overwhelming majority (89 per cent) do not have access to paid sick leave.

The likelihood of a job providing paid sick leave appears to increase with pay, however, even those earning between $40,000 and $50,000 per year—close to the median (or middle) income —just over half do not have paid sick leave. Only workers earning $50,000 or more fare better—and even among the highest earning group ($100k-plus), about a third do not have access to paid sick leave.

The close connection between lack of paid sick leave and low earnings poses a significant challenge in our fight against COVID-19. Many of the lowest-paid workers in BC are those in frontline retail, food services and care jobs that involve working in close physical proximity to others. Asking these workers to stay home when sick shifts onto them the cost of protecting public health, costs they may not be able to shoulder and that threaten to plunge them into poverty (or deeper into poverty).

And while the new temporary Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) is nominally available to workers quarantined or sick with COVID-19, it only covers those who miss so much work that they earn $1,000 or less in a pre-defined four-week benefit period. Importantly, CERB will not cover lost income for most workers who stay home with cold or flu symptoms but test negative for COVID-19 and are able to return to work within a week or so. It will also not cover workers who have the misfortune of getting sick just before the end of a four-week benefit period and have their illness spread over two benefit periods. This is why we continue to see people going to work sick.

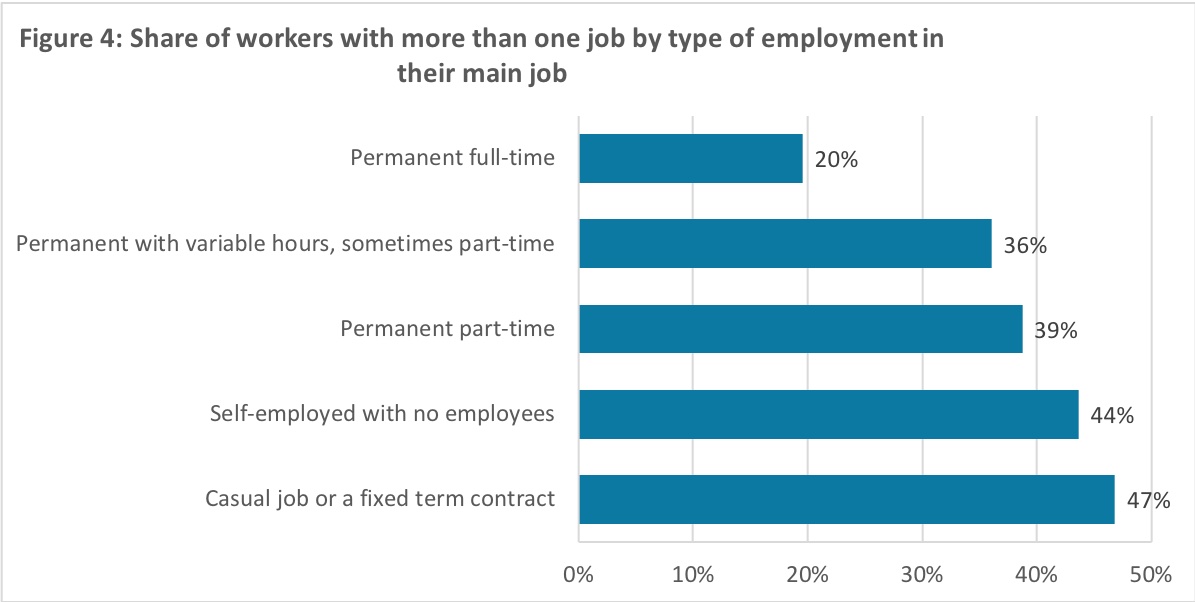

Some types of jobs provide less access to paid sick leave

British Columbians with full-time, permanent jobs are the most likely to have access to paid sick leave. However, nearly half of working British Columbians—44 per cent—did not have a permanent full-time job pre-pandemic. Among those with short-term employment contracts (less than a year) or in casual/on call positions, over 90 per cent did not have access to paid sick leave. And, of course, the self-employed largely lack access to paid sick leave altogether.

Unionization substantially improves access to paid sick leave

Two-thirds of unionized workers in our survey reported having paid sick time while the reverse is true for non-unionized workers. This highlights the importance of collective bargaining for securing better working conditions and the need to remove barriers to unionization for workers—particularly for those in low-wage, precarious sectors of the economy.

Likely because of high levels of unionization, public sector workers had significantly more access to paid sick leave than those working in the private for-profit sector (68 per cent vs 37 per cent respectively). Half of non-profit sector workers had paid sick leave.

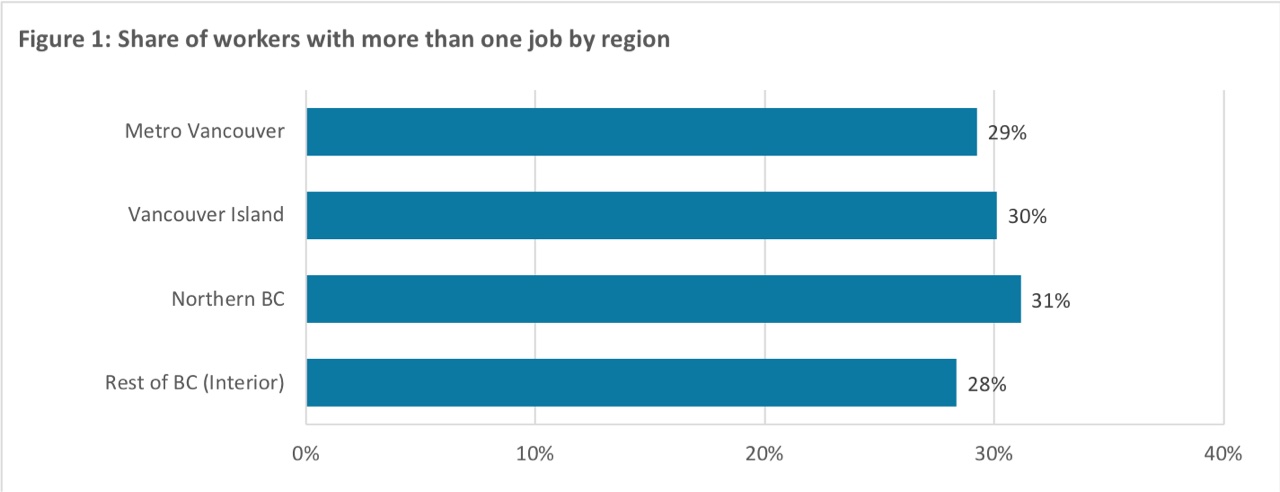

Substantial regional differences in access to paid sick leave

Our survey also revealed considerable regional differences in access to paid sick leave. Metro Vancouver had the highest proportion of workers with paid sick leave (50 per cent), followed closely by Vancouver Island (47 per cent) while the Interior of BC had the lowest at 37 per cent. It is worth noting that workers living in the City of Vancouver had significantly lower access to paid sick leave—only 46 per cent—compared to those living elsewhere in Metro Vancouver (53 per cent).

Workers in lower-income households tend to have very poor access to paid sick leave regardless of where in the province they live and work, but those in the Interior were worse off than in other regions. Only one in five workers in households with income below $60,000 had access to paid sick leave in the Interior compared to one in three workers in similar households elsewhere in BC.

Middle- and higher-income workers in Northern BC and the Interior are much less likely to have paid sick leave than their peers in Metro Vancouver and Vancouver Island. This is likely driven by the industrial differences in regional economies, as employers in goods producing industries like forestry, mining, construction and manufacturing are less likely to provide paid sick leave (even to middle- and higher-paid workers) than employers in service-producing industries.

Our survey revealed that workers in manufacturing, construction, trades and transport work and those in primary sector industries (including fishing, farming and natural resource industries) were less likely to have access to paid sick days than those who were employed in service sector jobs or knowledge and creative work jobs.

Who are the workers with no paid sick leave?

Men and women reported equally poor access to paid sick leave. Racialized workers reported slightly lower access to paid sick leave than Caucasian workers but the difference wasn’t statistically significant. Indigenous workers, however, were much less likely to have paid sick leave than their Caucasian peers (63 per cent vs 52 per cent, respectively). Although our sample of Indigenous workers is small (a total of 121 respondents), their lack of access to paid sick leave is a concerning finding.

Nearly two-thirds of respondents who were permanent residents (63 per cent) and three quarters of those with temporary status in Canada (75 per cent) worked in jobs with no paid sick leave compared to 52 per cent of Canadian citizens.

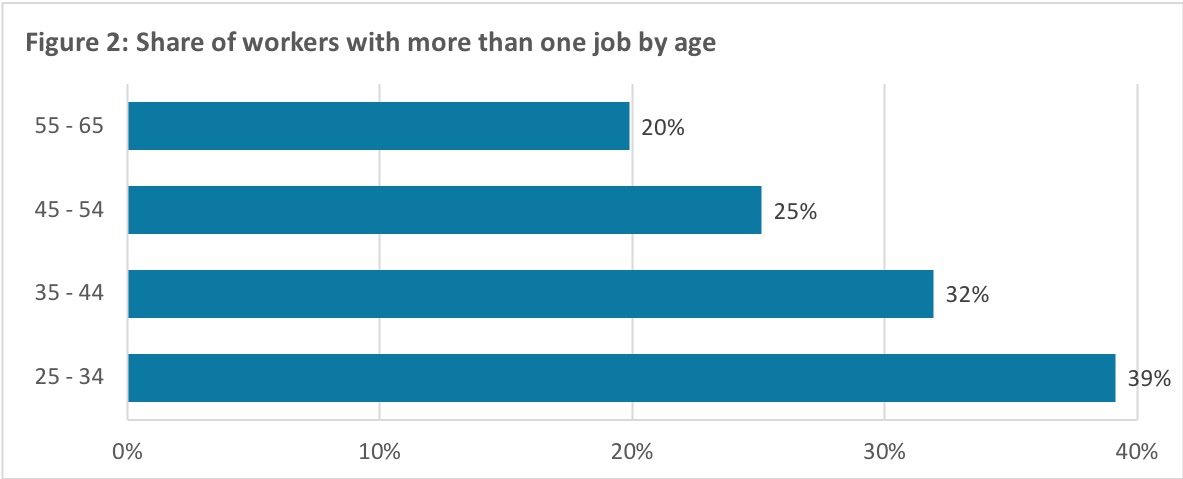

Significant differences do exist by age. Workers aged 45-54 are most likely to have paid sick leave (56 per cent) and older workers aged 55-65 are the least likely to get it (40 per cent). Notably, the low access to paid sick leave among older workers is driven by older men who have the least access to paid sick leave of any group (only 34 per cent). In contrast, older women have significantly better access to paid sick leave (47 per cent), better even than younger female workers (43 per cent). This could be related to higher levels of public sector employment among women.

Jobs that don’t provide sick leave were also much less likely to offer pensions (or employee contributions to RRSPs) or other benefits; a small fraction (13 per cent) of workers who don’t get paid sick leave receive pension benefits from their employers compared to 76 per cent of those who do. As a result, workers without paid sick leave are also more likely to have to save for retirement (if they can afford it) and to shoulder other expenses like a dental or healthcare, making time off work even less affordable.

“We simply don’t know how many Canadian workers did not have access to paid sick leave from their employer before the pandemic.”

Who are the workers with no paid sick leave?

Canada only collects data on employer-provided benefits on an ad hoc basis and while these data are available to academic researchers, Statistics Canada does not report on them publicly and they are therefore not widely used by policy-makers or in the public debate. In contrast, the United States Bureau of Labour Statistics collects annual data on employee benefits and publicly reports it disaggregated by industry and income level, showing that among the lowest-paid 10 per cent of American workers a whopping 70 per cent didn’t have access to paid sick leave in 2019.

We simply don’t know how many Canadian workers did not have access to paid sick leave from their employer before the pandemic, where they worked or how much they earned. Extrapolations can be made from the monthly Labour Force Survey, as done by CCPA’s David Macdonald, but the data available there only reflect sickness-related absences that were at least a week long and we know that cold- or flu-related symptoms can often resolve faster than that. The lack of regularly collected and publicly reported data on access to benefits in Canada represents a concerning gap in our understanding of the job market and how it is changing over time.

Legislated paid sick leave is essential

Without paid sick leave, workplace-based outbreaks could be a major obstacle in the fight against COVID-19 as we gradually reopen the Canadian economy. They might even become the determining factor in how quickly we can go back to normal, with workplace-based outbreaks potentially forcing a return to stricter “lockdown” style measures. If people can’t afford to stay home when they are sick this impacts not just their health but the health of their communities.

Paid sick leave is both an essential right for workers and essential public health policy—during the pandemic and beyond. Paid sick leave will likely reduce the spread of other contagious diseases, including the flu, at any time. This is why most wealthy countries require employers to provide at least some paid sick leave, and many have introduced additional paid sick leave provisions for the duration of the pandemic.

“Without paid sick leave, workplace-based outbreaks could be a major obstacle in the fight against COVID-19 as we gradually reopen the Canadian economy.”

Keeping workers out of workplaces when they are sick will come with costs and workers exercising more caution during the current pandemic will increase those costs. Putting all this on the shoulders of workers is unfair—it is up to employers and governments to step up and ensure, for the greater good, that we can all stay home when we are sick. There are ways for governments and employers to share costs now during the pandemic while many employers are also struggling so that workers are able to take sick time confident that they will not be penalized.

A new sick leave policy must provide all workers with an entitlement to short-term paid sick leave at their usual rate of pay so that on the day that they wake up feeling unwell they know with certainty that they will not lose income if they stay home. This is best achieved under provincial employment standards legislation. Having to submit an application for coverage under a special program administered by the federal Employment Insurance (EI) or the provincial WorkSafe BC systems would create unnecessary administrative burdens, carries the possibility of the claim being denied and may result in delayed payments that are also generally lower than workers’ regular rate of pay—in the case of current EI sickness benefits, for example, only 55 per cent of regular earnings. Without full protection against loss of income, staying home when sick will remain out of reach for too many low-wage workers.

Canada needs new, permanent paid sick leave rights for all workers funded by employers, which should come with a mechanism for governments to provide relief to employers currently struggling as a result of the economic crisis. In the short term, due to the corona virus a longer paid sick leave benefit will be required, but adequate paid sick leave should be a permanent policy change that lasts beyond the pandemic. The long-term economic recovery will depend on a comprehensive and equitable policy solution that protects all workers, and their communities, from the risks of going to work sick.

Table: Access to paid sick leave in BC by selected worker and job characteristics, 2019

CCPA-BC commissioned the BC Employment Precarity Survey in partnership with SFU’s Labour Studies Program. This internet-based survey was administered by Insights West in the late fall of 2019 to British Columbians between the ages of 25 and 65 who had worked for pay in the previous three months. The survey, which replicated elements of the PEPSO survey of workers in Ontario, was designed to collect more information on job quality and workers’ experiences of insecure and precarious employment than Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey covers. A total of 3,117 qualified respondents completed the survey. Weighting was applied to the data according to Statistics Canada 2016 Census figures on region, age, gender, ethnicity and among the Chinese and South Asian populations, country of birth and time in Canada among immigrants to ensure it is representative of the working BC population between the ages of 25 and 65. A true probability sample of this size would have a margin of error of plus or minus 1.8 per cent 19 times out of 20.

We thank the following organizations for their financial support of this research: Vancity Credit Union, the Vancouver Foundation, BC Federation of Labour, Federation of Post-Secondary Educators of BC, the Lochmaddy Foundation and the UBC Sauder School of Business.