To reduce gender inequality, introduce paid sick leave

In the week of International Women’s Day let’s celebrate BC’s positive steps toward gender equality while bringing attention to the changes still needed.

When it comes to gender and (paid) work, one recent big achievement is the BC government’s introduction of job-protected paid leave for workers who experience sexual and domestic violence. In March 2020, the Province enhanced existing employment rights for survivors by introducing five days of employer-paid leave per year (all previously provided leave had been unpaid).

This right applies to both part-time and full-time employees regardless of how long they’ve been employed. Importantly, the right to paid leave for survivors of violence exists under the BC Employment Standards Act. This means it is a statutory minimum that applies to every worker in BC and is enforceable in cases when employers deny someone their right to a leave, or reprimand someone for taking it. While not perfect, the new right to paid leave from work is a step closer to addressing one dimension of gender inequality in employment given that women—especially Indigenous women and girls and gender-diverse people—are more likely to experience domestic and sexual violence. And, during COVID-19 there has been a 20% to 30% increase in rates of gender-based and domestic violence.

Much more work remains to be done to achieve gender equality in the workplace.

We could talk about the persistent gender pay gap (women in BC earn on average 81 cents for every dollar earned by men), and the earnings gap is even greater for women with disabilities, racialized, Indigenous and newcomer women. We could also talk about the gap in promotions to decision-making roles recently documented by the Globe and Mail’s Power Gap investigative series, the shortage of affordable and accessible child care, harassment at work, or the recent mass firings experienced largely by women in BC’s hotel industry. All of these issues are deserving of attention and making progress on them would bring us closer to gender equality. However, given that we’re still in the midst of a global pandemic, let’s start with addressing a pressing public health matter: the lack of a legislated right to paid sick days, forcing too many working women in BC to make the impossible choice between losing pay and working while sick.

Paid sick days are a feminist issue

Paid sick days are a feminist issue

Research from the BC Employment Precarity Survey (conducted in late 2019 by Iglika Ivanova and Simon Fraser University Labour Studies Professor Kendra Strauss) reveals that over half (53%) of workers in BC don’t have employer-paid sick days.

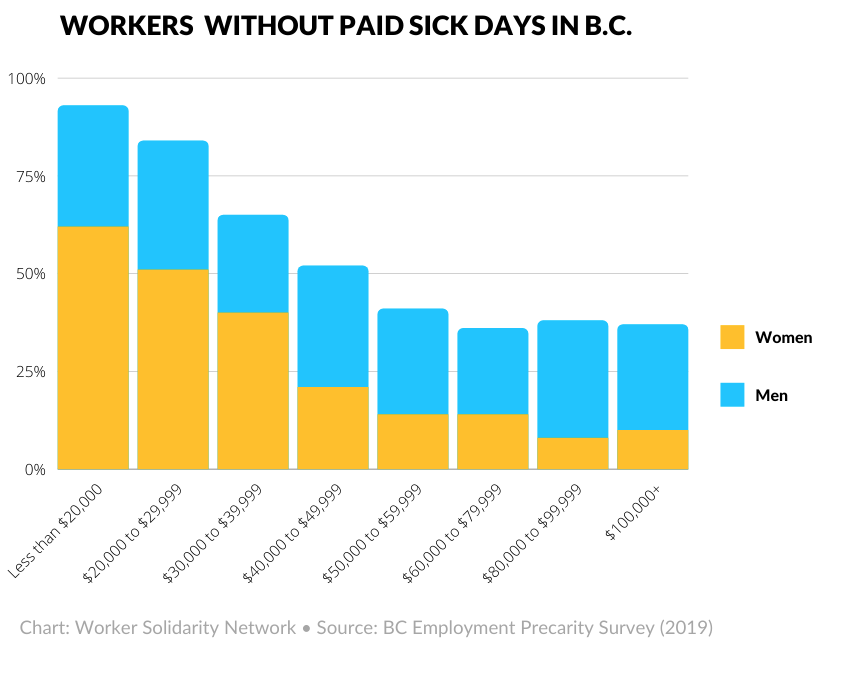

The lower your income, the less likely you are to have access to the option of taking a paid sick day when you get ill or need to self-isolate due to exposure to COVID-19. This is a problem because the systemic undervaluing of jobs where women are concentrated—care workers, cashiers, cleaners, servers—means these jobs have become low-waged work. Many workers who became the pandemic’s front-line heroes overnight are not only underpaid, but under protected.

An alarming majority of low-income workers—81% of workers earning under $40,000 per year and 89% of workers earning under $30,000 per year—don’t have paid sick days.

Women are a lot more likely than men to be in these income brackets and make up 64% of workers in these income ranges who don’t have paid sick days. Given that racialized workers are also often over represented in precarious, low-wage jobs, this is another important reason to be alarmed by the connection between the absence of sick days and low-income employment.

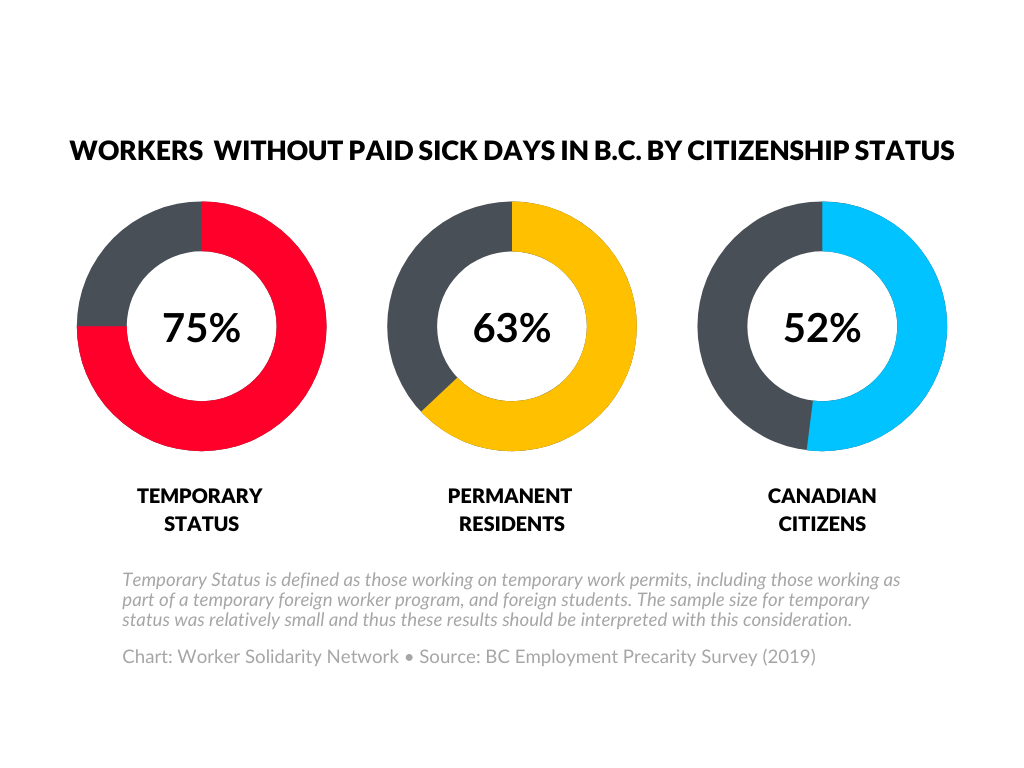

Immigration status is also significant when it comes to access to paid sick days in BC. While 48% of workers with citizenship status report having paid sick days, this figure drops to 37% for permanent residents and just 25% for workers with temporary status (those working on temporary work permits, including as part of temporary foreign worker programs or foreign students). Women represent the majority (58%) of non-citizen workers without paid sick leave.

It is clear that low-income, vulnerable women will be the biggest beneficiaries of legislated paid sick leave.

But the need for a statutory right to paid sick days is a feminist issue for yet another reason.

School and daycare closures during the pandemic disrupted the (constructed) divide between paid and unpaid work. As women continue to do more child and family care work in the home, this disruption of women’s work has been another gendered consequence of COVID-19. Federal data reveals that women make up 62% of the applicants to the Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit, which provides income support to people who cannot currently work because of child or family care responsibilities.

During and post pandemic, access to paid sick days could lessen the economic burden faced by women who are likely to be the ones to need time off work to care for sick children when they must stay home from school or daycare.

The Canada Recovery Sickness Benefit, the federal program for people unable to work because they are sick or must isolate due to COVID-19, is not a solution to the need for paid sick days. It lacks the flexibility of paid sick leave (because it needs to be taken one week at a time), doesn’t fully replace lost wages and requires workers to wait before getting paid, a burden too high for low-wage workers living paycheque to paycheque. Plus, it’s a temporary problem that only applies to COVID-19 while workers need protection from income loss when they are sick with other illnesses too. That’s why the BC Employment Standards Coalition and the Worker Solidarity Network are calling for the introduction of paid sick days under the BC Employment Standards Act, where, like the paid leave for survivors of domestic and sexual violence, the right can become a permanent, enforceable, statutory minimum that applies to all of BC’s employees.