Partner Spotlight Series Interview with Pioneer Activist Cenen Bagon

by Sumaiya Tufail

How did you get involved with Vancouver Committee for Domestic Workers and Caregivers Rights (CDWCR)?

I got involved with the issue of domestic workers in 1979. We were activists in the Filipino community, educating our community and the rest of mainstream Canadians about the realities of the dictator former President Ferdinand E. Marcos’ repressive government, marked with human rights violations, extrajudicial killings tortures, disappearances and incarcerations. We met domestic workers who were abused by their employers and that’s when we started helping domestic workers in Vancouver. With domestic workers and allies we collectively created an organization called the Committee For the Advancement of the Rights of Domestic Workers (CARDWO) in 1979. Those we met were not only from the Philippines but also from other Asian countries, Latin America and the Caribbean.

When we were organizing and doing education work, similar to what we have today but with far fewer resources, we had the support of other communities who were also active in educating their own communities to the realities of their own repressive governments back home. Labour, feminists, farm workers, human rights and church organizations also supported the domestic workers’ call for landed status upon arrival. Similar to the organizing and supports happening in Vancouver, domestic workers were at the same time being organized in Toronto and Montreal.

At the time, domestic workers couldn’t apply for permanent residency. It was an immigration program for temporary workers; Canada would just hire temporary workers. The domestic workers wanted to become permanent residents, and through education and forums, we all agreed that domestic workers should come as permanent residents because their work is essential and permanent. Canadian families really need domestic workers and care workers to take care of their children, elders, and people with disabilities. Even then, domestic workers were needed in Canada. Therefore, if they are needed, they should come as permanent residents because the need is permanent.

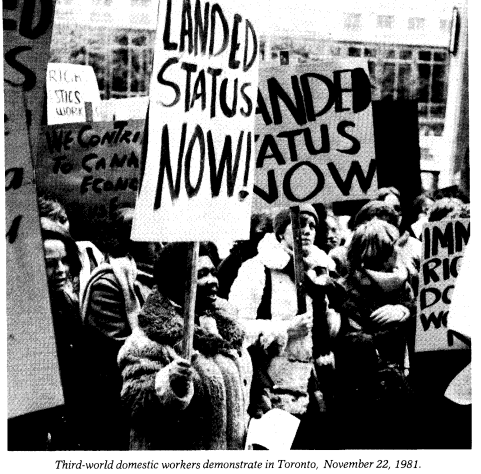

We emphasized to the government that because Canada did not have a universal child care program and relied on workers from other countries to care for the elderly and the sick, these workers should be granted permanent residency. The real highlight was these women were fighting for their rights at the time, setting forth the demand for landed status upon arrival. Up to now, it’s still the demand! We held rallies, did education work, and engaged in community work in Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver. In 1981, at the height of a major rally of domestic workers, the government implemented an immigration policy that allowed domestic workers to apply for permanent residency inside Canada. This was key in the whole struggle! Not everyone was able to get permanent residency due to the different requirements of the law. Each time the government reviews the immigration policy for caregivers, we always demand that the government grant caregivers permanent residency upon arrival. That is still our demand.

“If we are good enough to work, we are good enough to stay—landed status now.”

This has been our slogan since 1979.

Why does precarity matter to you right now and for the future?

We really wanted to eliminate the precarious nature of the care worker. For example, precarity starts when they arrive here because they are temporary workers which makes them more precarious in their already precarious working conditions. Employers can ask the worker to do anything, and the employee may not complain because they work inside their employer’s home and don’t have any other worker to talk to. It’s the workers’ word against her employers’. They are very isolated because they work inside the home, which adds to the precariousness of the situation.

Most of these women come from developing countries and could be very poor, so when they come here, they just want to work to support their families back home. Of course, if they are temporary, they will follow what the employer wants as much as possible. Sometimes they don’t know their rights because they arrive not knowing anyone else except their employers. If they come from the Philippines, they already have to have an employer before arriving, so they go directly to them.

We reach the workers through word of mouth; the government doesn’t want to share information with us. Let’s say a worker arrives in BC; the employer is supposed to register their worker in BC’s central registry, but we don’t know how the central registry is being used or if it’s a complete list because the government doesn’t share it with us.

Is there a particular project you’re excited about and why?

I’m excited about the policy paper that the Migrant Care Worker Project team will produce under the Understanding Precarity in BC project, being conducted jointly by SFU Labour Studies, Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives in BC, research community, labour and communities. After almost two years of research work, the team explored the intersections of immigration policy, racism and precarity for temporary foreign care workers, and as a result will report their research findings and create a care worker immigration policy proposal that will be submitted to the Federal government.

I’m also looking forward to the result of the BC government review of the Labour Relations Code – CDWCR submitted a sectoral bargaining proposal. Labour legislation is supposed to remedy the relationship imbalance between workers and their employers. But because of the precarity of care work, the current legal structure in British Columbia does not provide adequate safeguards against abuse by unscrupulous employers who exploit care workers for being temporary migrants and in-home workers. We proposed a sectoral bargaining model for sectors such as migrant care work, where workers are often individual, isolated, fragmented, and in precarious positions; a sectoral bargaining model where employers and workers will be represented at the negotiating table with a neutral government person (either from Labour Relations Board or from the Employment Standards Branch) as the chair.

Currently, a bargaining unit in BC is composed of workers under one employer. In-home care workers usually work alone at their employers’ homes. To negotiate with each and every employer of a care worker would be very tedious, expensive and yes, impossible! And what bargaining power does this kind of bargaining unit have during negotiation – can you imagine a strike action by one? The employer can just easily fire the worker!

We also proposed that the central registry be improved and be made accessible to the groups supporting care workers. Enhancements to the central registry ensure accountability and facilitate standard enforcement to improve the sector.

What has working at this organization taught you?

The main lesson I can think of is that we know this fight for the rights of migrants, care workers, and the marginalized is really hard work. We need to learn from the workers, and it always changes. Our lives are affected by different factors happening at the moment, so we need to analyze what is the best way to achieve migrant justice. It requires a thorough assessment of where we are as people, as governments, and how factors like racism, sexism, and classism are at work. All these things need to be considered in the analysis so that our fight and solutions are aligned with reality.